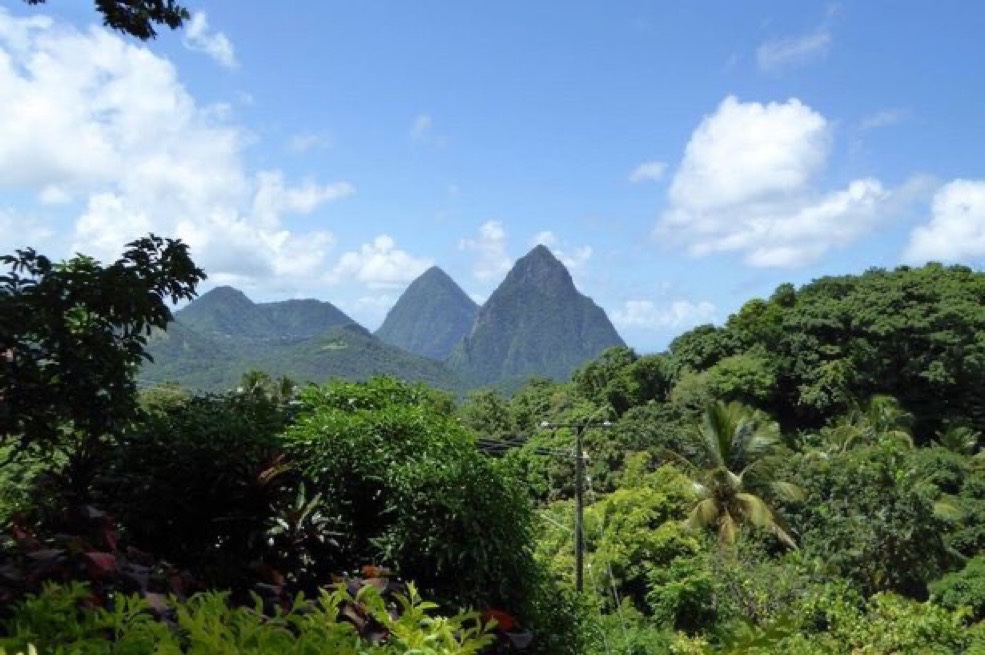

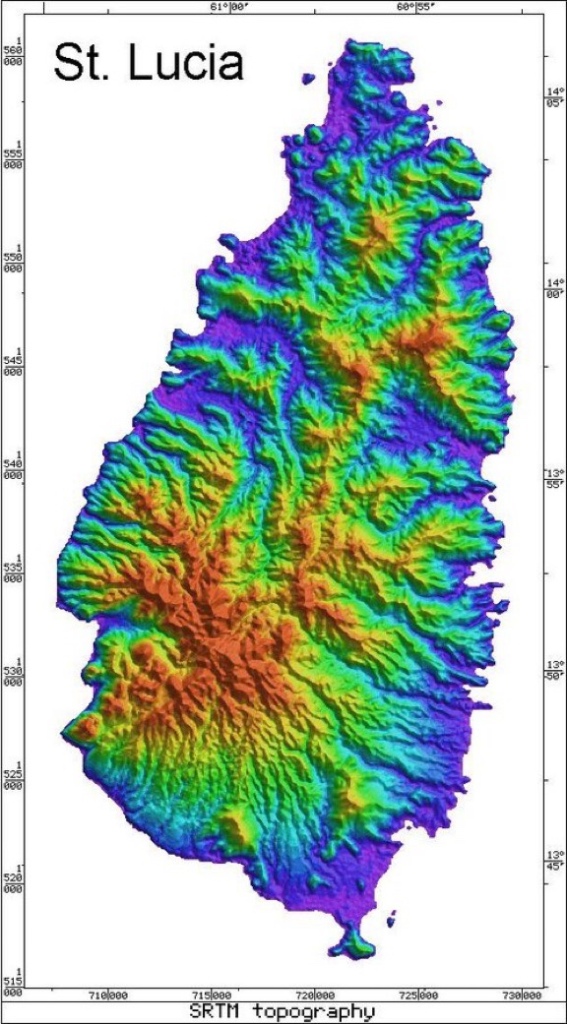

The Island of St. Lucia sits in the southern portion of the lesser Antilles and is the second largest of the windward islands. It’s is twenty-seven miles long and fourteen miles wide. Large volcanic peaks rise to more than 3,000 feet and split the island down the middle forming into a dense look on the islands southwestern coast. The eastern coast is filled with high rocky cliffs battered by large wind driven waves coming off the Atlantic. This side of the island is in a rain shadow, as moisture is forced up and over the high mountainous spine and creates a verdant tropical rain forest on the western slopes. The rain has carved great valleys where habitation and port access developed. This is especially true of the island’s northwestern coast, where the modern capital of Castries lies today.

Saint Lucia traditionally formed the outer defenses of French strongholds of Martinique and Dominica. It’s possession also helped the French project power south through Grenada. The British had taken Dominica in the previous conflict known as The Seven Years War. This new British possession was now surrounded by the two French islands of Martinique and Saint Lucia, with British possessions to the North and South. British held Dominica also severed lines of communication between Martinique and Guadeloupe.

After word of the American Alliance had reached the French Caribbean in August of 1778, preparations were immediately put into place to seize Dominica. Dominica’s population still spoke French and significant part of the militia were made up of Gens de couleur or free men of color. French agents quickly convinced the militia to refuse muster when called and sent about saboteurs to damage the fortifications around the capital of Roseau. The British authorities were not yet informed of the French alliance and had kept their fleet at Barbados.

Landing several thousand men on September 7th, the ill prepared British garrison was abandoned by their militia and had the gates of the local fortress unlocked by French agents. French forces quickly closed in on the capital of Roseau and occupied the heights surrounding the town. Roseau sits in a steep ravine at the mouth of one of the only accessible inland routes into the mountainous interior. The British position in Roseau was hopeless and naval support failed to materialize.

The Island fell into French hands and communication had been established once again throughout the French Antilles. The loss of the Island was blamed squarely on lack of naval support and the British quickly made plans to strike at St. Lucia. Veterans hardened by war in America were sent south throughout the fall and the fleet was made ready at Barbados. A successful attack on St. Lucia would place the British in position to strike at the heart of French power emanating from Fort de France on Martinique.

The British set sail from Barbados in early December and aimed their invasion fleet toward Saint Lucia, with 5,000 soldiers under Admiral Barrington. Disembarking in the Cul de Sac south of Castries, over 2,000 British troops swept north and secured Morne Fortune and Carenage Bay. French forces retreated into the dense jungle surrounding the capital region and awaited reinforcements. A large French Fleet under Admiral D’Estaing arrived the next day and British naval forces would have been lying in wait, had it not been for a storm on route from the American coast that slightly delayed their departure.

The French forces numbered twelve ships of the line and had 9,000 troops while the British fleet contained seven ships of the line and around 5,000 troops (Half had been disembarked during the initial invasion). Instead of pressing their advantage right away, the French dithered until the next morning. British forces used the evening to safely anchor their transports in The Cul de Sac and array their fleet in an arch protecting the mouth of the bay. Batteries had been erected at the headlands of both the Cul de Sac and Carenage Bay to the north.

The French tried to force Carenage Bay and the capital of Castries, but were repulsed by strong British fortifications on the headlands protecting the mouth of the bay. The fleet sailed south to attack the British transports anchored in the Cul de Sac, but failed to bring the full strength of their numbers to concentrate on any single part of the British defensive line of ships. Their attack petered out and the French fleet regrouped for a second attack at full strength, with all twelve French ships of the line being thrown at the northern end of the British anchorage. Here the British had placed their heaviest warships and were closely supported by strong shore batteries. The French numbers were negated by the small geographic space and placed under heavy fire by guns from the shore based fortifications.

Unable to make headway, the French fleet slipped away to the north over night and disembarked over 7,000 troops in Gros Islet bay (Rodney Bay). Marching south against the fortified headlands protecting Carenage Bay and Castries, the French faced formidable entrenchments on the Vigie pennisula (Pictured below). Manning the entrenchments were 1,500 experienced British veterans of the American Revolution, but they were heavily outnumbered by the French forces assaulting their positions. Largely recent recruits and Antilles militia, French forces faltered under constant volleys of small arms and grapeshot. After three valiant charges, 400 French lay dead and 1,100 were wounded compared to twenty-five dead British soldiers. The invasion force was pushed back to their ships and the fleet retreated to the safety of Martinique. The French forces still in the jungle surrendered to the British the next day, upon word of incoming British relief fleet. The Island became a jumping off point for the larger British victory at Les Saintes in 1782, but was returned to the French in 1784 after the war ended.